Inflationary risks have been building and central banks have started to respond. Will they go too far?

Central banks walk the tightrope between inflation and growth

Global stock markets have benefitted over the past year from a potent combination of three factors: abundant liquidity from central banks, fiscal spending from governments and a powerful surge in corporate earnings. These three forces have combined to push markets higher with unusually low volatility. Company earnings have been so strong this year that even as markets have rallied, valuations have fallen. This is quite normal for this stage in the cycle but is certainly welcome given the elevated valuations in some equity markets, notably the US. But all good things must come to an end and in September most of the major central banks signalled that it’s time to start reining in monetary stimulus. The Federal Reserve has announced that it will be winding down its QE programme, most likely starting in November, whilst the Bank of England has signalled that it is going to start raising interest rates in the coming months.

Over the summer central banks had been steadfast in their view that the pickup in inflation is temporary and likely to recede as the year progressed. This confidence has been wavering, with one of the regional US Federal Reserve Presidents saying that he’s banned the use of the word “transitory” and that staff members have to put a dollar bill in a jar each time it is used. Jerome Powell, chair of the Fed has stated that “The risks are clearly now to longer and more persistent bottlenecks, and thus to higher inflation”. One of the problems for central banks is that they cannot solve these supply-chain problems: they cannot produce more goods or control commodity prices. Powell went on to say that “Supply constraints and elevated inflation are likely to last longer than previously expected and well into next year, and the same is true for pressure on wages. If we were to see a risk of inflation moving persistently higher, we would certainly use our tools.” However, for now the Federal Reserve are only inclined to reduce QE, with Powell stating “I do think it’s time to taper; I don’t think it’s time to raise rates”.

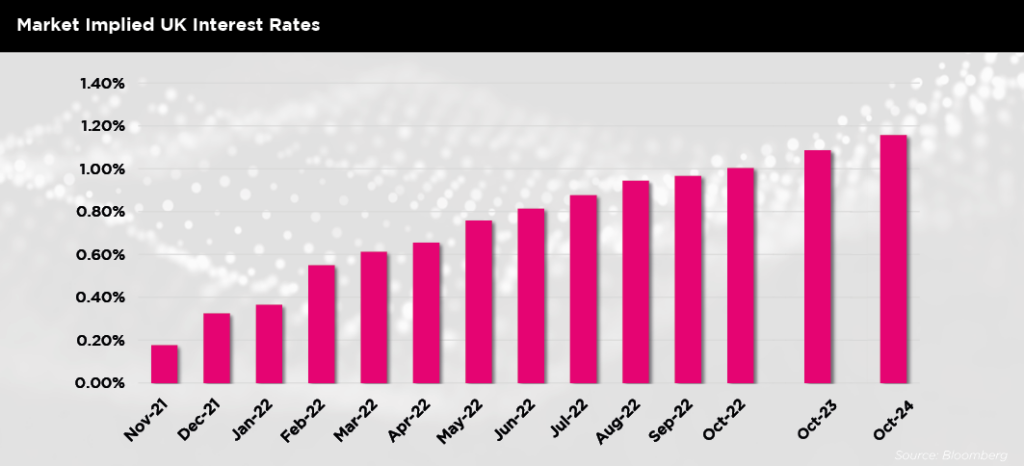

Whilst the major central banks typically move in packs, the Bank of England seems to be acting like a lone wolf, opting to raise interest rates well ahead of the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank. The market now expects interest rates to rise from 0.1% today to 1% by this time next year. This has surprised some commentators, especially as the Chancellor has signalled that fiscal spending is also going to be curbed. Does this mean that interest rates are going to rise sharply over the next few years? We don’t think so. With the amount of debt in the UK system, even relatively small increases in interest rates could cause a sharp slowdown in growth: Bloomberg Economics estimate that the 0.55% increase in 5-year government bonds we’ve seen will reduce GDP by 0.8% over the next 12 months. So, the Bank of England can raise rates modestly, but aggressive rate hikes would cause growth to stall. This may explain why markets forecast that interest rates can’t get much above 1% over the longer term. We think that the recent changes in rhetoric from the Bank of England and others is more about maintaining credibility in the face of rising inflationary pressures rather than a step change in interest rate policy.

Battery powered

Whilst the long-term outlook for inflation remains uncertain, there are other areas of the macroeconomy that we can be more certain about. It’s clear to us that climate change is going to be the key issue for policy makers over the next few decades. It is now an inescapable fact that the ecological, human and economic impact of climate change will shape the world for decades to come. Failure to act raises the risk of damage from extreme weather that will occur not only more frequently, but also more severely. This would displace people, put huge pressure on the supply of goods and food, and ultimately cause widescale economic scarring.

Two key components on the road to a net zero world are the replacement of the internal combustion engine in cars and the move to renewable energy. Electric vehicle sales have surged in the first half of 2021 by 160% in the three top auto markets of the US, China and Europe. Decarbonising our energy systems has been accelerating over the last two decades, with countries such as the UK making significant strides to move to renewable sources for energy production. However, the recent surge in energy prices has highlighted the underinvestment in the energy generation sector broadly, and some of the specific challenges of renewable technology. Energy storage is required to smooth out any mismatch between supply and demand for power.

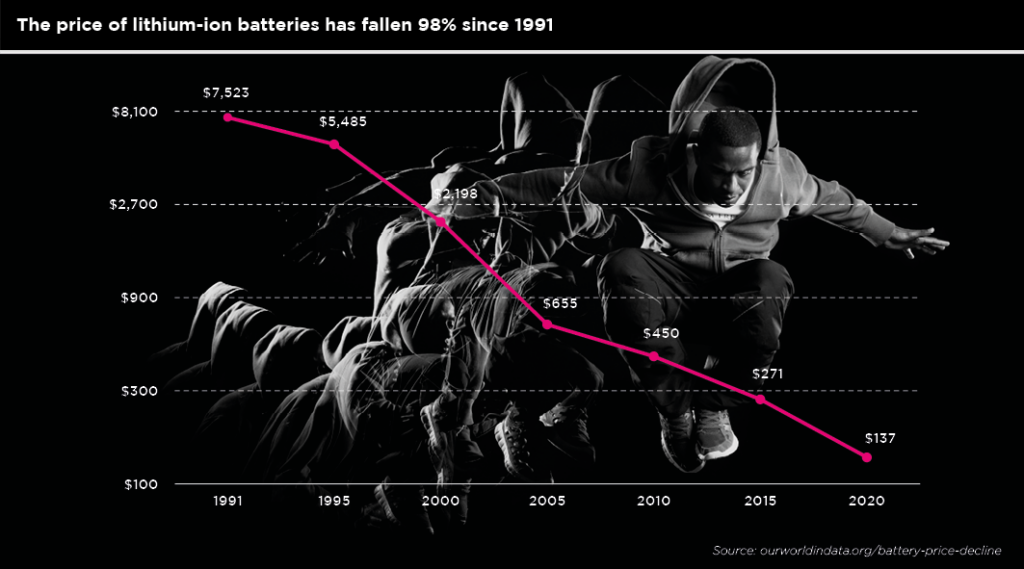

A key part of the solution to these issues is addressed by the humble battery. Batteries have come a long way since they were invented by the Italian physicist Alessandro Volta in 1800. Prices (per kWh) have collapsed over 98% in the last 30 years and continue to fall year on year. For example, the battery in the Nissan Leaf electric car costs around $5,500; a battery with the same power would have cost $300,000 in 1991. Commercial battery storage operations, which store energy produced via renewables to smooth energy supply is also a huge growth area, with BNEF expecting a 23% annual growth rate over the next 5 years. As the move towards renewable energy grids and electric vehicles increase, the World Economic Forum forecasts battery demand to increase 14-fold over the coming decade.

Some battery technologists also point to the fact that the global fleet of electric vehicles (EVs) may literally serve as the world’s battery; perhaps, revolutionising the economics of power generation. This is through technologies such as Vehicle-to-Grid Integration and Bi-Directional Charging. Vehicle-to-Grid Integration allows EVs to be less of a burden by optimising consumer charging habits. For example, EVs can be charged overnight during troughs in electricity demand, rather than during peak early-evening hours. Bi-Directional Charging is even smarter, allowing EVs and utility companies to form a relationship whereby EVs are charged when electricity is abundant and cheap, and utility companies ’pull’ electricity from EVs when required. The implications of this relationship are vast, and they solidify batteries’ position as a key pillar of a decarbonised future. Companies such as VW and Nissan are already implementing this technology into some of their EV cars.

Conclusion

Two of the key drivers of markets in the future are the outlook for inflation and the response to climate change. Inflationary risks are building, and central banks will need to walk a fine line: maintaining credibility by responding to a pickup in inflation without choking off growth. Given this backdrop, it’s important to build diversified portfolios that can thrive should inflationary risks grow. In terms of climate change, it is clear for us that this will be one of the key themes in terms of fiscal spending and government policy for decades to come. We look to areas that are set to benefit from these changes and find that batteries will prove indispensable in the transition to a low carbon economy.