- Central banks have indicated that whilst interest rates are close to peaking, they will need to remain elevated to bring inflation down.

- The combination of large government deficits, a lack of central bank buying and “higher for longer” is pushing bond yields higher.

- Longer term this is positive for investors as they are being properly rewarded, once capital values stabilise.

- In the meantime, it’s important to have a range of diversifying assets that are uncorrelated with bonds and equities which benefit from higher cash rates.

Outlook

Central banks are signalling that the end of interest rate hikes is in sight but once we reach the top, it will be like scaling Table Mountain – we won’t be heading down any time soon.

It has been nearly two years since the major developed central banks started raising interest rates. In a breathless ascent, rates have increased from the lowest in human history to levels last seen in the mid-2000s. The rate hiking cycle in the US has been the fastest since the early 1980s when Volker was stomping on the last flames of the inflation bonfire that one of his predecessors, Arthur Burns, had allowed to get out of control in the 1970s. This time round, none of the central bankers want to be remembered for failing to push rates high enough, for long enough, to bring inflation back under control. So, they are threatening to keep interest rates at restrictive levels for long enough to smother this latest inflation wildfire.

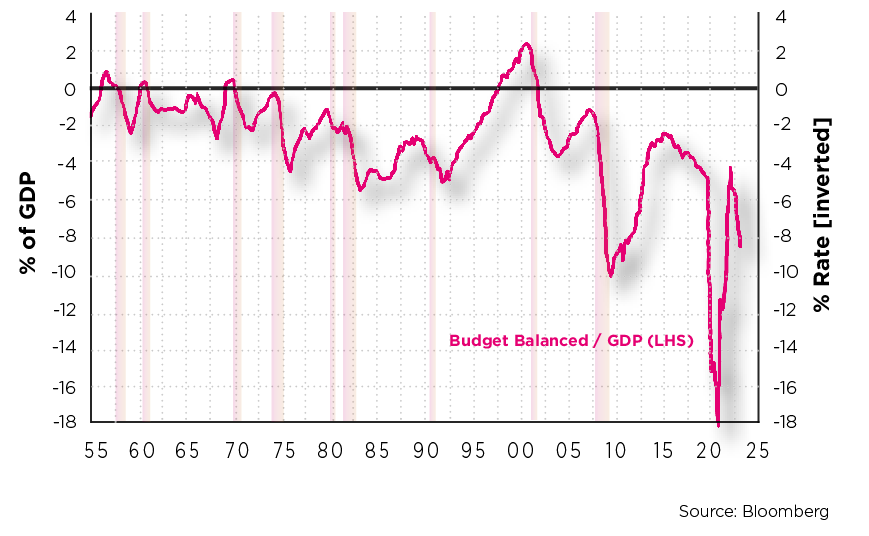

Whilst interest rates may be close to peaking, removing one stress from the minds of market participants, the bond market is anything but calm. For most of the last decade, central banks’ influence has been felt not just in interest rates, but also in the yields of all bonds with their gargantuan bond buying (QE) programmes. This pushed down bond yields to ever lower rates enabling bond issuers from corporates to governments to issue debt at record low yields. The poster child was the Austrian government who issued a 100-year bond at a yield of just 0.85%. As the borrower, the government, has done rather better than the lender (the buyer of the bond) who has seen the bond price drop from 100c to 35c, all for less than 1% of income a year. The days of absurdly cheap borrowing are long gone. Today, QE has ended and is now being reversed through Quantitative Tightening (QT) and so one of the largest buyers in central banks are notably absent. Meanwhile, governments have got a taste for spending, having seen its awesome power during the pandemic, and are spending more than they are receiving in taxes at a record rate. It’s not unusual for governments to run a deficit, but outside of a recession or a world war, this level of spending is unprecedented in modern times. As a result, governments are issuing large numbers of bonds and, without central banks buying up those bonds, investors (lenders) are demanding higher yields. Thus far, economies have also been resilient to this hiking cycle, with consumer spending remaining robust, business activity remaining positive despite negative manufacturing survey data, and the labour market is yet to show sustained weakness. This has furthered the resolve of central bankers in ensuring the message of ‘higher for longer’ and has served to be another catalyst for bond yields to rise.

Implications for Portfolios

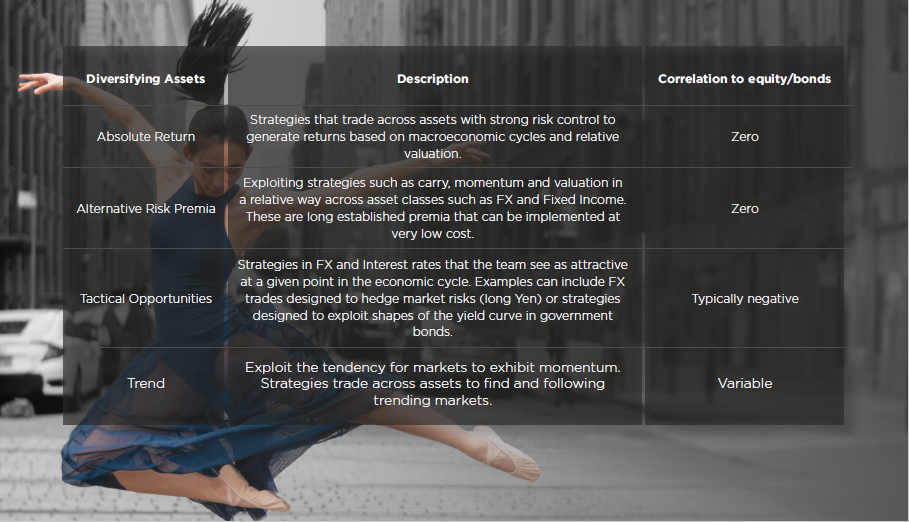

In the long term, as investors in bonds this is good news – as lenders we are being much better rewarded for risks. But of course, in the short term, rising bond yields mean falling prices which can more than offset their income. And as equity valuations are impacted by longer dated bonds, there’s a risk that equities and bonds move in unison as they did in 2022 so, it’s important to have assets portfolios that are uncorrelated to both equities and bonds. We broadly refer to these strategies as Diversifying Assets, and classify these approaches as follows:

Having multiple approaches to diversifying assets provides a further source of diversification which allows for scaling up and down sub strategies depending on the environment. We believe that these strategies will remain important for managing risk, but also for generating returns that can be competitive with the major asset classes. One of the reasons for this is that they benefit from this environment of higher interest rates for longer as they earn the cash rate on top of the performance of the strategy itself. Given the central bank hiking cycle to date, this has become a very attractive tailwind for these assets – with cash rates at around 5% in many major economies. Cost of access is also an important consideration, in past years alternative asset managers were able to charge high fees for such approaches, drastically reducing their return potential (especially when cash rates were low), whereas now many diversifying asset strategies can be implemented at very low cost. Overall, there has been a marked change in the opportunity cost to hold these types of strategies, and they stand to benefit portfolios from both a risk and return perspective.

Conclusion

Investors can have short memories, and recently bonds have not provided the protection they did in the preceding decade whenever equity markets were weak. The re-pricing has meant that on a long-term basis, investors will stand to benefit from bonds again. In the interim, we think that an emphasis on diversification is important. Adding diversifying assets to portfolios, that can generate strong returns independently of the moves in fixed income and equities will be vital for robust investor outcomes going forward.