- Market performance in early 2024 was strong, driven by strong macro data and themes such as AI, but recently volatility has emerged.

- This year’s global elections are the largest ever, but some are less free and fair than others.

- Historically, elections have had limited long-term impact on markets at a global level, however surprise results can affect local markets.

- Ongoing political volatility, particularly in the US, may influence markets, but fundamentals such as the strength of the global economy and company earnings remain more crucial.

Outlook

Market performance was strong in the first half of 2024, fuelled by economies at full employment, continuing wage growth, strong consumer spending and a small rebound in those sectors that had been most affected by rate hikes. The AI theme also powered US stock markets to all-time highs. However, the summer has seen a return of market volatility, as a rotation away from many of the equity market’s winners (the magnificent 7 stocks) and a rally in the Yen. This has primarily been caused by slightly softer economic data combined with crowded positioning in markets by some investors. This is a reminder that market volatility can often come from seemingly nowhere.

One of the key aspects of this year, that we highlighted in January, was the scale of elections that would take place over the course of the year. In fact, 2024 is set to be the largest election year in terms of the number of people going to the ballot box in history, roughly half of the world’s adult population.

However, as we discussed at the time, the freeness and fairness of elections has shifted. Since the end of World War 2, there has been an incredible drive towards liberal democracy across much of the world. However over the past decade, this wave of democracy has been receding. This includes overt shifts to greater authoritarianism in places like Russia, where all semblance of political opposition has been eradicated over 20 years, as well as more subtle removals of rights to minorities in certain nations.

This, combined with a rise in political populism and polarisation means that market participants have been attempting to understand the implications of elections on emerging market such as Mexico and Taiwan, but also across both the UK and US, and other major developed economies.

A history of election impacts on markets

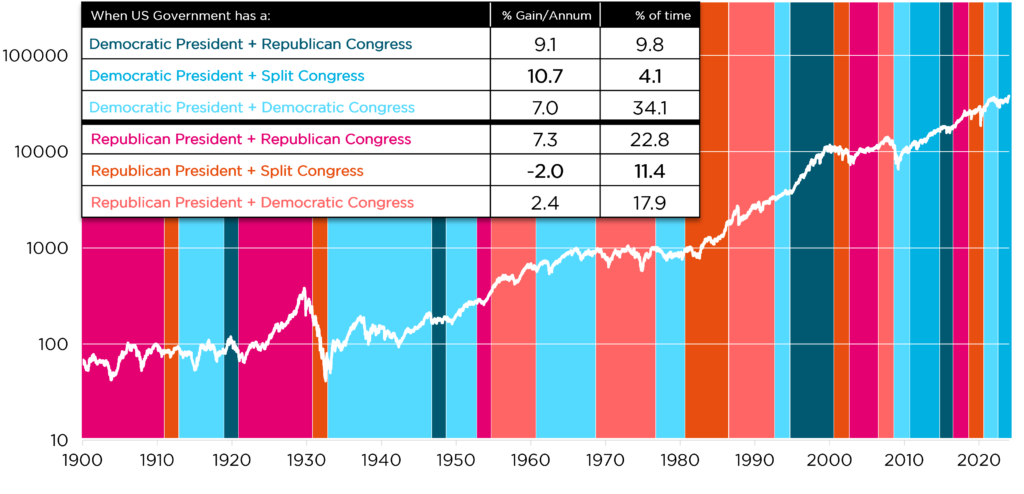

History however teaches us that elections, whilst vitally important to foreign and domestic policy, matter less to markets. When we look at the performance of markets over four-year presidential cycles, we see that returns are often strongest both in the year prior to an election and in the immediate period after an election takes place. This may well be because governments spend more money in the run up to elections and then tighten their belts once they take office.

Furthermore, when we dissect the average performance under different governments, we see that Democrats with a split congress perform strongest in market terms, whilst Republicans with a split congress perform weakest. Often, therefore, gridlock is seen as less of an issue and more as a continuation which can help markets, which obviously tend to rise over time.

When we look back at the history of the stock market, there are surprisingly large differences in the returns from Democratic Presidents versus Republican presidents, particularly when congress is split. However, it’s clear that luck, or rather bad luck in the case of the Republican party at the start of the Great Depression, plays a part.

When do markets perform the best?

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P

Current state of elections

This year has brought its fair share of electoral surprises. For example, a strong showing in the presidential election in Mexico from Sheinbaum, who is viewed as being on the left of the spectrum and not market friendly, caused a sell-off in the Mexican Peso and Mexican Equities. The same was true in India after a worse than expected showing from Modi, which normalised after he agreed to form a coalition government.

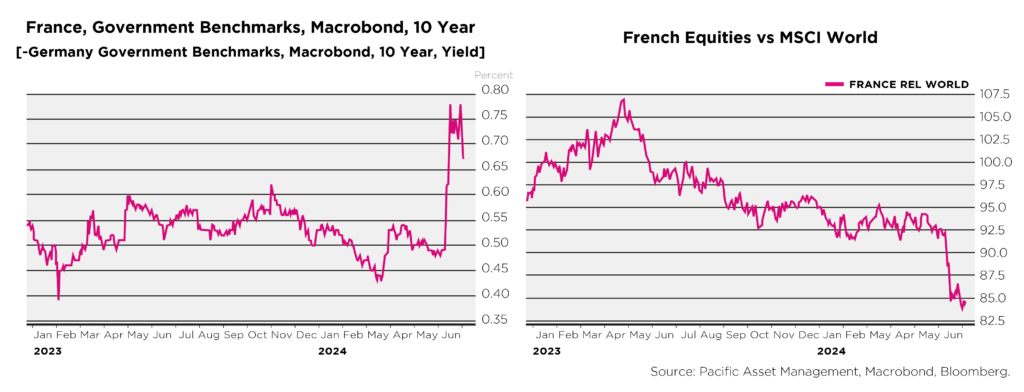

One election that we did not forsee was in France, where President Emmanuel Macron decided to call a snap legislative election after a poor result in the European Parliamentary elections. In these elections, the National Rally party, headed by Mariene Le Pen, took more than one third of the seats. During the two-round system, the far left and centrists pulled candidates to try to prevent an outright win for the National Rally party. The far left won, with 188 seats, whilst the centrists won 161 and the far-right won 142. Given that no one will work with the far-right faction, this hung parliament situation is likely to lead to policy stalemate. The effect of both rounds is that French bonds have sold off relative to German bonds, and French equities have also underperformed.

The UK, saw the lowest election turnout since 2001, and a change of government after 14 years of the Conservatives being in power. The country finds itself in a tricky position, with historically low growth, and a constrained fiscal position. Neither the Labour nor Conservative party wants to increase spending or lower taxes significantly, having seen the havoc that could be wrought in the bond market by unfunded spending during the Liz Truss leadership. Given attractive valuations relative to the rest of the world, however, it is hoped that political stability can increase interest in the UK as a destination for overseas capital.

In the US, the election campaign has been fraught, punctuated by more and more unbelievable twists and turns. First, a poor debate performance brought into question President Biden’s fitness to run as president, given this was a race between the two oldest candidates in Presidential history. This was followed by an attempted assassination attempt of former President Trump, which likely surged his popularity in the polls. Most recently, Biden announced he was dropping out of the race, leaving Vice President Kamala Harris the Democratic candidate to take on Trump.

Of course, in policy terms, there remains a considerable gulf between the candidates, with Trump likely to seek greater tariffs on Chinese exports (or even a global tariff on goods), as well as talk of weakening the dollar to improve US competitiveness and changing US policy stance on issues such as supporting Ukraine in its fight against the Russian Invasion. A Democratic government under Harris would likely be a continuation of Biden’s policies.

What may not change under either possible government is that fiscal spending is likely to remain at elevated levels. Under both Trump and the Democratic administration, spending increased dramatically, helping to extend the growth cycle but at the cost of higher level of inflation. This fiscal stimulus pushed the budget deficit to levels not seen outside of recessions or wartimes and, for now at least, represents a new normal in managing a country’s financing.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we would likely say that political volatility will persist throughout the year. What matters more for markets, over the medium term, is their fundamentals, such as the strength of the global economy, company earnings and valuations. However, it’s important to monitor political developments, as shocks can affect markets and decisions such as fiscal spending can have a significant impact on growth and inflation.