Why international investors in bonds and equities alike turned sour on Brazil in 2024.

Fiscal Domination could be a word to remember for years to come – not just in Emerging Markets.

The situation in Brazil has potential read across to other countries including (perhaps surprisingly) India which, relative to debt outstanding, is the most leveraged Emerging Market.

Brazil’s market collapse: What went wrong?

In 2024, the worst-performing major equity market in the world was Brazil. In US$ terms, the benchmark Bovespa index dropped almost 30% while nearly all global markets delivered solid positive performance. There was no coup or natural disaster in Brazil, economic growth was decent by Brazilian standards, and unemployment reached a record low. Brazil isn’t particularly exposed to US tariffs, and Donald Trump has not yet made claims on Brazilian territory. So, what went wrong?

The cost of capital and investor confidence

A core tenet of North of South’s investing philosophy is the cost of capital. When domestic bond yields rise, the fair value of domestic equities declines. They become less attractive relative to fixed income alternatives, and we become more concerned about potential currency risk.

A high rate of interest demanded by investors in domestic government bonds is a function of the risk of default (inability of the government to pay back interest and principal) and currency devaluation (the flipside of higher long-term inflation). Both can impose losses on US$-based investors in local currency debt.

Fiscal domination: An expression to remember

What was exceptional last year was that the Brazilian central bank started raising rates in opposition to the rest of the world and reversing its incipient easing stance. Combined with intransigence from President Lula on government spending, this led to “fiscal domination” – an expression to remember for the coming years.

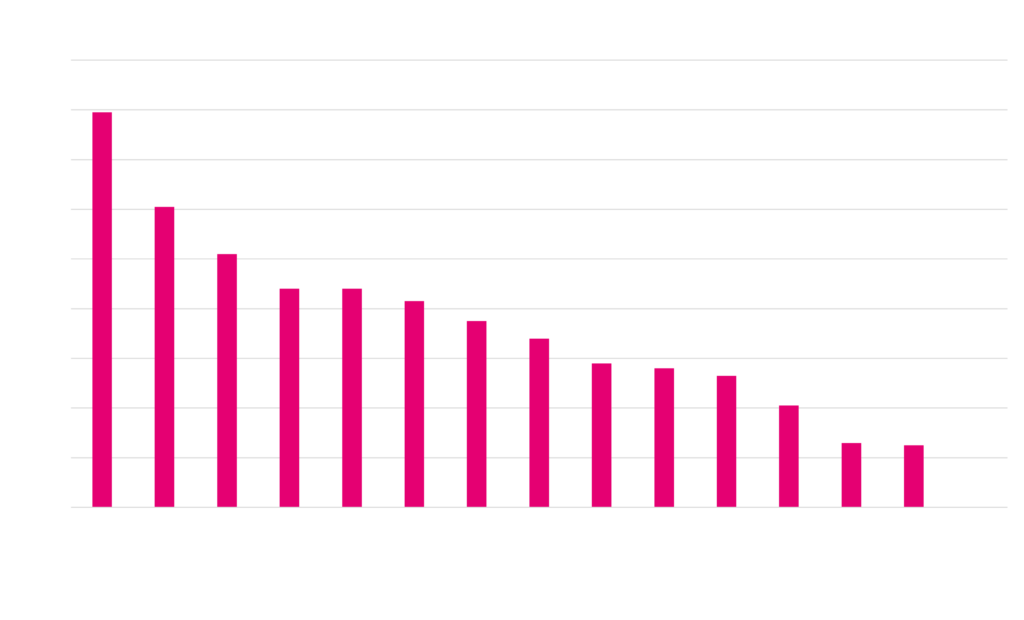

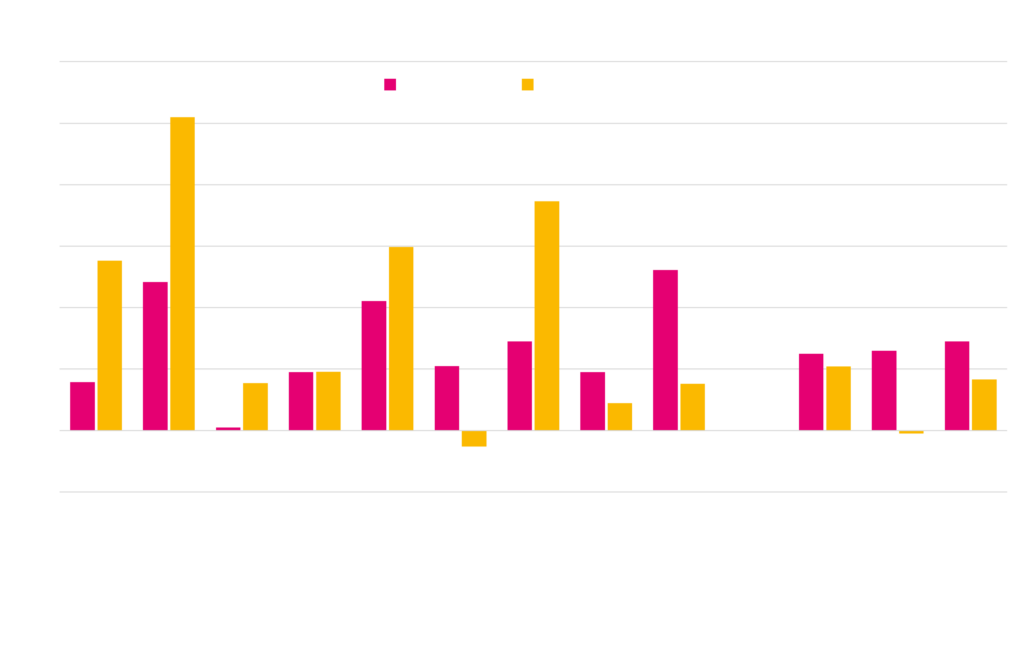

Investors often look at a government’s debt/GDP ratio as an indicator of financial health. This can be misleading as context is needed. Japan is nonchalantly running its debt to GDP ratio at over 240%, three times as high as Brazil, without any visible concerns from financial markets. More important is the expected direction of that ratio and the avoidance of a debt trap where additional leverage is needed to meet interest costs on existing debt.

Source: IMF

Why debt/GDP ratios alone don’t tell the full story

There are two factors that determine how high debt/GDP can rise without causing a debt trap. One is nominal GDP growth (growth + inflation) – as long as this exceeds the deficit, debt/GDP will fall. The other is the level of domestic interest rates.

Japan’s debt burden is manageable because interest rates are only around 1% (10-year bond yields currently at 1.2%). This means only 2.5% of GDP is needed to service the debt – among the lowest in the world. Greece benefits from low Euro rates and has been able to reduce debt/GDP from 190% in 2018 to below 160% by running budget surpluses and delivering growth.

What keeps interest rates manageable?

There are three ways real interest rates can remain low, even for a country with high debt/GDP:

- The World’s Reserve Currency – The US benefits from this unique position.

- Excess Domestic Savings – Countries like China, Taiwan, and Germany have high household savings that can be channelled into their bond markets.

- International Investor Confidence – This is where Brazil has struggled, as fiscal concerns have undermined foreign investment.

Brazil’s debt spiral and the risk of high rates

Even as inflation remained modest at around 4%, the Brazilian Central Bank reversed its accommodating stance, raising rates from already elevated levels. This was prompted by concerns that GDP growth was keeping inflation persistent. Brazil also suffers from low potential growth due to lack of investment and deteriorating demographics.

Source: IMF

Although the Brazilian government runs an almost balanced budget before interest costs, the high level of interest it pays on its debt pushes it into a significant budget deficit of about 9% of GDP. Lower nominal GDP growth of around 7% (inflation at 4% and real GDP growth of 3%) means annual increases in the debt/GDP ratio, further pressuring the government budget in a vicious circle.

The impact of policy decisions on market confidence

President Lula’s tone-deaf approach to this problem has further undermined confidence. Even with an aggressive Central Bank policy and intervention in FX markets, the deterioration of the government’s ability and willingness to balance its books has led to sharp declines in the Brazilian Real. This has led to the moniker of “fiscal domination” – the government’s budget trumps all other indicators and actions, even by the Central Bank.

One may have some sympathy with President Lula’s predicament. If Brazilian rates were lower, Brazil could be paying down its debt and creating a virtuous circle – but unfortunately, they aren’t. Building market confidence to bring down borrowing costs is as much an art as a science.

Source: IMF

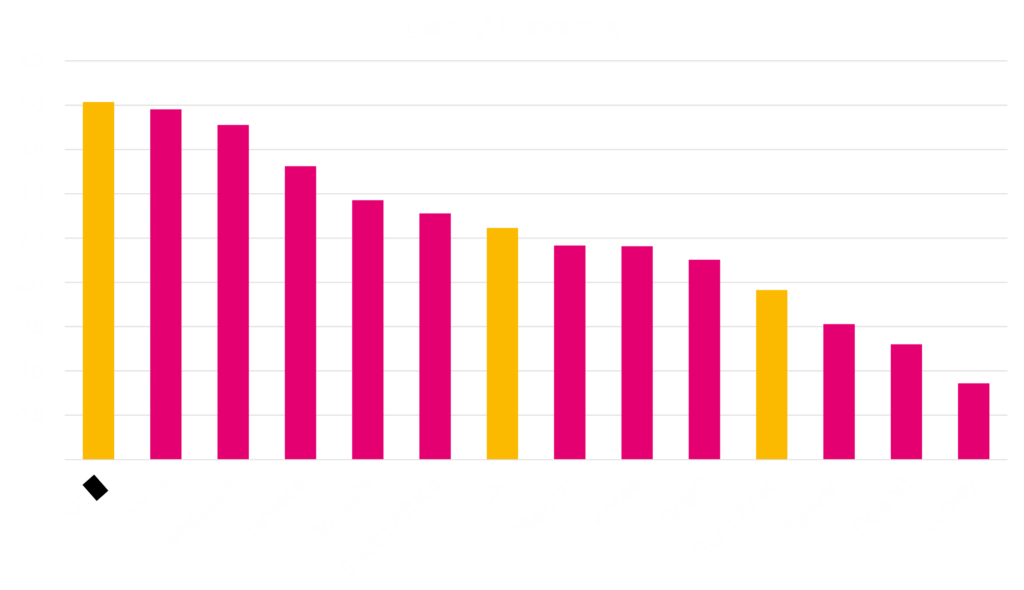

Could other emerging markets face a similar fate?

While Brazil’s problem is well understood and to some extent priced in by the market, it is worth considering other countries that could find themselves in a similar situation.

- South Africa has high interest rates and a budget deficit, but recent political shifts have reassured investors.

- India has strong growth but carries total government debt exceeding 80% of GDP, with low tax collection limiting fiscal flexibility.

- Malaysia, Greece, and Indonesia have benefitted from growth and low rates but could be vulnerable to changes.

The self-fulfilling nature of debt markets

While countries like the US and Japan seem to be able to push government debt levels with impunity, other nations testing the limits of debt carrying capacity may find that it doesn’t take much to push them over the brink.

The good news is that just as markets can push a country into a negative debt spiral, they can also reverse what seems like a hopeless situation. High rates attract investors, who, by driving them down, can pull a country back into a sustainable trajectory. However, the higher the debt outstanding, the greater the risk of miscalculation.

For now, Brazil remains the most vulnerable major market and a real test case for how fiscal domination may play out elsewhere.

[1] Source: CEIC