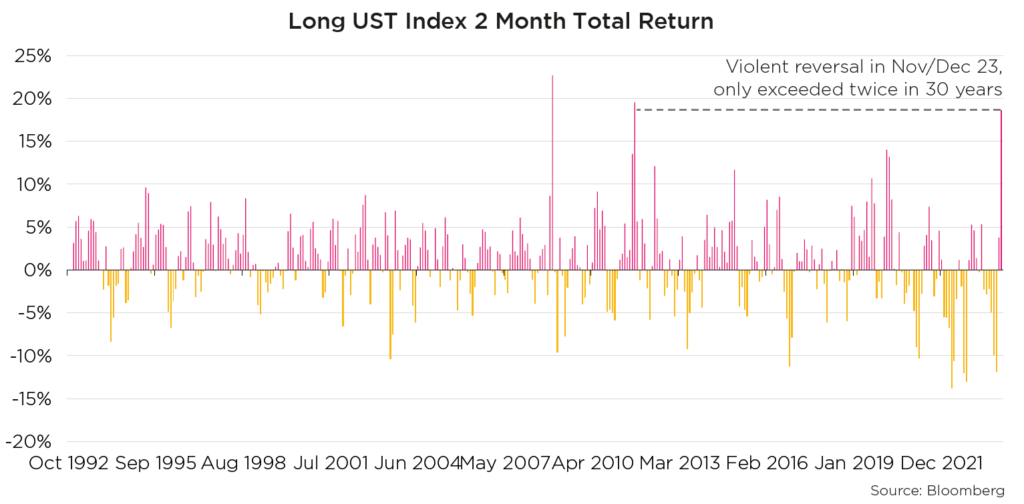

2023 encompassed the extremes of the recent global rate hiking cycle. The peak yield in the UST 10y rate of 5% at the end of October, sharply reversed on the Fed pivot to finish the year almost where it started at 3.88%. However, this nil sum round trip doesn’t reflect the years real story – of central banks wrestling back control over inflation. Many thought this bogey man had been laid to rest by Volcker many years ago. With their inflation fighting credentials severely damaged in recent years, it was imperative that they regained the initiative and market confidence of their ability to rebottle a genie that had escaped the magic lamp.

What have we learnt from this battle?

For most G10 central banks there was no easy option in fighting inflation, other than face the problem head-on with a sustained series of hikes between 4-500bp which had not been experienced for 40 plus years. Interestingly, it seems in general the starting date or pace and path of hikes had little bearing in combating inflation in comparison to the net magnitude. Some of those central banks who started earlier and paused (RBA and BoC), eventually were forced to increase again in the prolonged battle to take the heat out of, initially a lack of supply induced, then a demand led, inflation blow-out post covid.

History will judge whether the signs for a first time in multi decade inflation spike were obvious or not. However, the ingredients were hidden in plain sight. Covid fiscal priming, QE, exceptionally low rates, covid lock down enforced household savings increase and then the unleashing of the pent up desire to catch up on life. Combined with industrial shut down and then slow to reopen production scale amongst delivery bottlenecks. The real surprise was just how slow the central bankers were to take away the “punch bowl” when the party was in full swing. They are unlikely to make the same mistake again, and going forward will err on the side of policy conservatism for choice.

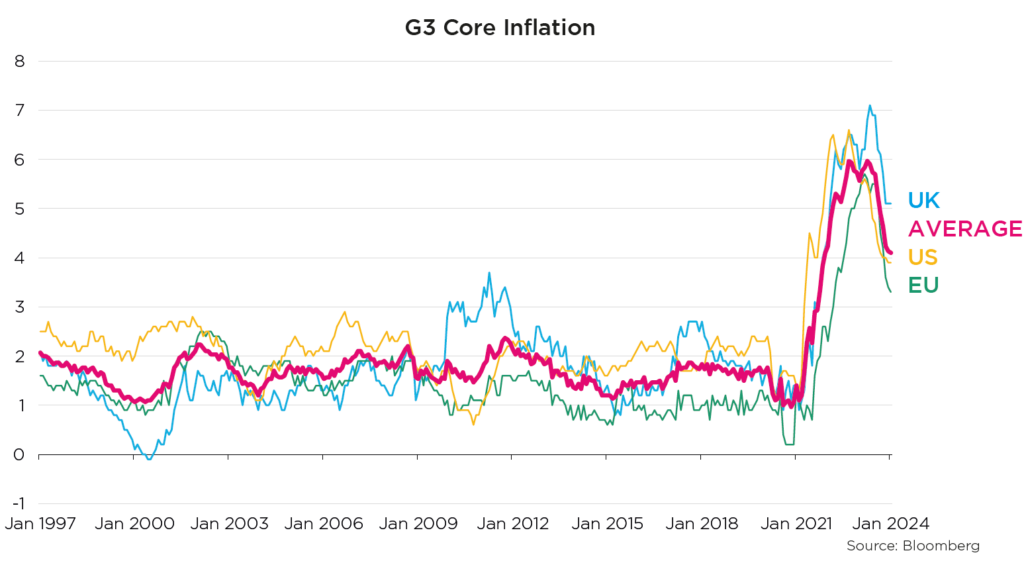

The markets first mistake was expecting a reopening boom in China similar to the recent western pattern. This failed to materialise as housing (being a popular store of wealth) was weakening, and the lack of a social security net during covid had increased household savings and reduced consumer demand and sentiment. The biggest mistake by the market in G10 was a continued belief that the impacts of the hikes would transmit rapidly through the economy and induce a global recession. Primarily due to greatly underestimating the impact of fiscal programs, and the extent of household savings increases via stimmies and enforced inactivity during lockdowns. These, along with secure job growth were able to maintain a high level of consumer demand and continued to confuse and confound the hard landing narrative throughout the year. In retrospect – the direct pass through of literal helicopter money to households is somewhat more effective to sustain economic momentum than trickle down via the banking system. For nations that suffered the worst of the energy shocks, such as the UK, the persistent nature of inflation and second round effects like increased wage demands become commonplace and entrenched once critical headline levels are breached. Even though headline inflation has dropped on the back of food and energy base effects, core inflation is still elevated. This predicament leaves central banks hampered in the pace or extent they can cut rates for the time being.

Implications for the future?

We believe the coming year will be dominated by the push and pull of a market pricing rate cuts versus conservative central banks trying to control those expectations.

Bond returns have been volatile, unpredictable and frustratingly correlated to equities in recent years. A mixture of very large deficit financing combined with less financial repression via the end of QE has put pressure on term rates and with some dire consequences. The glaring lack of oversight or regulatory bite over Silicon Valley Bank will undoubtedly change the hands off approach to regional banks previously taken by their fed authorities. In conjunction to rectifying the blatant ignorance of economics 101 of duration exposure on long dated accrual portfolios. A more interventionist monetary policy will equally be fighting corporate and commercial mortgage financing models likely to be more technically robust and longer in duration, but also governments that have embraced fiscal policy as an intrinsic part of modern (populist?) governing. The recent budget setback in Germany will be a case in point as they seek postponements of constitutional diktats to a balanced budget and carry on supporting the economy regardless. Another event to note will be the predicted change in the UK government by Autumn 2024. It may test the patience of the bond vigilantes again, as the incumbent government is pursuing tax cuts, despite initial fiscal warnings from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in an effort to retain power. Indeed, the same risk to higher bond yields applies across much of G10 when considering financing debt mountains accelerated from Covid emergency spending but also fiscal packages such as the giant US IRA and Chips Acts.

The US may find its unique funding advantage as the worlds base currency being challenged as higher rates in Japan draw their domestic investors towards JGB yields, and an increasingly rebel BRICS try disengaging their USD reliance. It is notable the slide in global USD FX holdings to an all-time low of 59%.

Re allocation of financial resources is a growing factor. Climate change pledges are warranted, urgent and expensive. The scale of the enterprise necessary to wean the world off fossil fuels, which is measured in US$ Trillions, will undoubtedly change the investment landscape. Another sector that will also be a draw on capital will be an increase is defence spending. As western democracy increasingly feels threatened, the cost of defending it shall increase. The long budget holidays enjoyed by Europe in this sector is over. Their reliance on US is now on tenterhooks with the presidential election in 24. NATO needs to prepare for change, and thus Europe needs to be self-sufficient and that requires many including Germany to step up. The Pacific region also requires investment in its military as China continues to push its sphere of control. The multi-billion dollar Australian nuclear submarine project SSN-AUKUS is just the start.

In terms of macro-economic forecast, dispersion is expected. The synchronised rate hiking cycle is now over. It is time for economies to differ in their monetary policy normalisation of rates according to their idiosyncratic energy dependency, strategic defence needs, fiscal policies, debt dynamics and consumer behaviour.

Fund Performance

The Pacific G10 Macro Rates Fund was able to successfully navigate an extremely challenging 2023, returning positive 6.28% in its USD Z share class. Notably the fund made 1.95% in March 23 when many macro funds suffered significant drawdowns due to the US regional banking credit shock. In doing so, the fund continues to express a high degree of non-correlated returns when analysed versus core markets and peers. This is primarily due to approaching investing from a broad portfolio of volatility weighted mean reverting trades across a range of products within liquid G10 markets. The new economic phase should benefit the Pacific G10 Macro Rates Fund as the differences in timing and scale of forward rate moves will probably differ greatly between the members of G10, and present ample trading opportunities. As a strategy that relies on diversification and mean reversion, having less interdependent economies and policies should only increase our portfolio divergence and potential returns.