From green transition to energy security…

Just when the world seemed to believe that widespread adoption of renewable energy was the only option, the war in Ukraine seems to have put this at risk. Is the transition to sustainable energy to blame for surging energy prices?

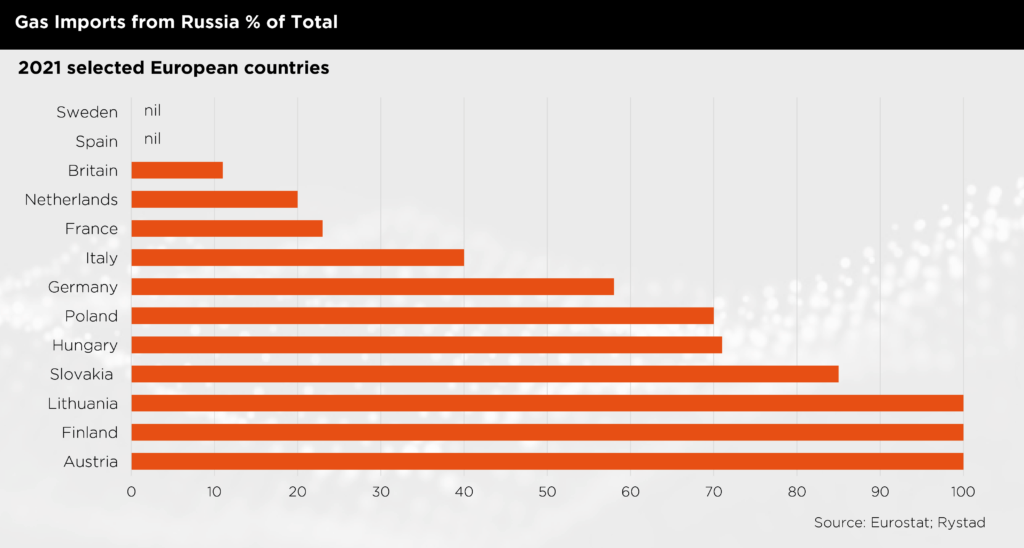

We are in the midst of an energy crisis, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and subsequent pariah status possibly removing 10% of global oil from circulation almost overnight.

But prior to this, it was clear that the energy complex already had a problem. European natural gas prices and power prices had surged over the course of 2021. In fact, the whole commodity complex was facing issues prior to the invasion, with prices for soft commodities (such as wheat and soy), metals such as steel and copper and fossil fuels all surging from their depressed 2020 levels.

In the post COVID world, a heady combination of fiscal stimulus and quantitative easing had meant that demand for goods had risen (and thus commodities used as inputs for these goods), whilst simultaneously their supply has fallen. There is a large swathe of industries where production was lowered because producers thought the impacts of COVID would be longer lasting. Additionally, global transport networks shuddered to a halt as Coronavirus restrictions at ports and airports meant that transporting commodities and components became very difficult. The knock-on effects of these supply chain disruptions have confounded market participants and central bankers alike in terms of their length and breadth.

Given the limitation of Russian supply for developed markets after sanctions – the supply/demand imbalance is

clearly getting worse. In simplistic terms, this could be viewed as a good thing. The commodity price rises may

start to accurately reflect the costs on the world of these emissions from fossil fuels and make renewable energy

much more competitive on a relative basis. However, in the short term, this is painful for consumers as prices will rise, impacting lower income households the hardest. Higher energy bills erode consumers ability to spend on other necessities and are a key cause of the “cost of living crisis” that we see today. It can take years to bring on additional supply of renewables, so as such this supply and demand in-balance could be long lasting, as could its effects.

Some market commentators have been blaming the ‘Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) revolution’ for the problems that Europe, and global commodity markets now face. Many have said that because investors are now concerned about the economic and social impacts of climate change, they are preventing investment and therefore limiting supply in commodity markets at precisely the wrong time, and that the move towards a greener society is the cause of the inflation woes that we see currently.

We do not feel that the current issues we face are primarily the fault of sustainability policy. If this narrative continues however, it is possible that the world turns its back on fighting climate change, and again refocuses on short term energy production as the ‘least bad’ answer to the current inflationary pressures developed economies face.

Energy policies often take decades to materialise, and yet the focus of investors on ESG only came to the fore in the last few years. We would point to two key issues that have had far more bearing on the current situation we find ourselves in:

- Private markets – fossil fuel producers have structurally burnt capital over the past decade – and this hasn’t been forgotten by profit maximising investors.

- Public policy – European fiscal controls have led to a structural underinvestment in infrastructure

Private Markets

For decades, oil, and other fossil fuel commodity production was dominated by the OPEC countries. However, in the mid-2000s new shale extraction technology meant that the Americas brought online massive supplies of oil. However, the companies that drilled this oil were individually smart but collectively stupid, bringing on excess capacity which drove down prices. As a result, they burnt through $300bn of investor capital over the course of the past decade through leveraging up and overproducing.

Now, with oil rising they have had to move to a capital disciplined business model to attract and retain investors – it is still good old-fashioned capitalism in action. A survey by the Dallas Fed of 132 oil and gas executives notes that 59% cited investor pressure to maintain capital discipline as the core reason why they are restraining growth despite high oil prices, with ESG only figuring for 10% of the results. As a handy excuse to the question, it is surprising more didn’t opt for it.

Public Policy

In public policy, we can point to Germany as an example of the problems we now face. German fiscal rules have for years hampered their ability to grow and invest in much needed energy infrastructure. European power demand has been increasing, and yet Germany has been unwilling to invest in its infrastructure for decades, and it is showing. This is further worsened by the Federal/State delineation in Germany, where States can often dictate a lot of spending. Germany first started importing Russian Gas in the 1960s, and its dependence on Russian natural gas has been widely understood since the mid-2010s. It’s reliance on natural gas increased after it cancelled its plans for expansion of nuclear power in the wake of the Fukishima crisis in 2011.

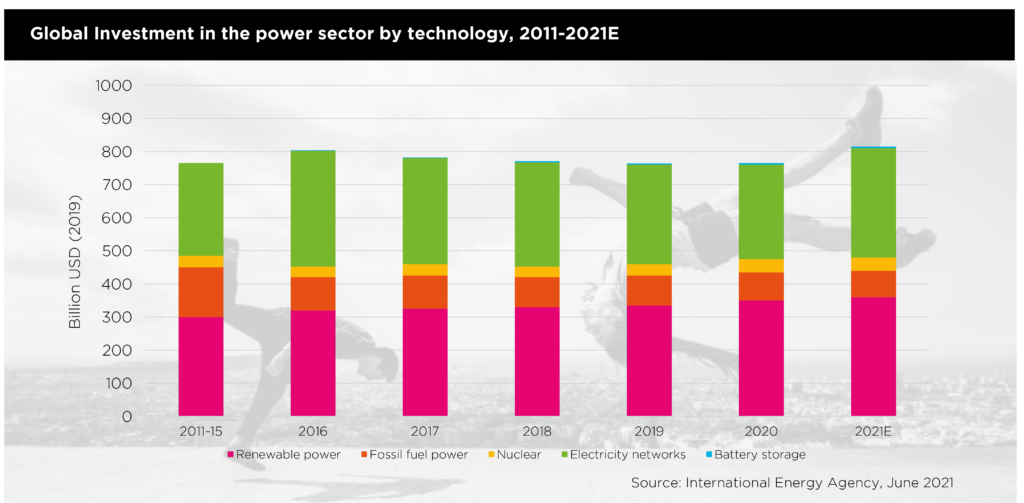

European, but particularly German policy has been characterised by underinvestment in a diverse power mix. However, this is not just a German problem but a worldwide one, with this chart below, from the International Energy Agency showing that global energy investment has essentially flatlined since 2011. Couple that with an electricity grid that in the US averages 40 years old, and you have a deeply insecure energy market. They estimate that energy investment will have to triple by 2030 to meet demand.

The good news is that this energy insecurity has focused the mind of policy makers. Germany has brought forward its goal of 100% Renewable energy production from 2050 to 2035 and has committed to investing $220bn by 2026. This does not just mean using solar and wind however, but also offsetting or capturing carbon emitted by natural gas, for example. This is a big structural change in fiscal policy for Germany, and the funds will go towards climate protection, hydrogen technology and expansion of the electric vehicle charging network.

Conclusion

We have witnessed a severe dislocation in commodity markets, which has driven energy prices to extreme levels particularly in the Euro area. This has heightened concerns about inflation and consumers’ cost of living. In the short term it has been geopolitics that has lowered supply and heightened volatility. This imbalance has also been caused over the medium term by a failure of capital discipline by fossil fuel companies and by an underinvestment in infrastructure by governments. All of this was compounded by the macroeconomic impact of Coronavirus, which fractured supply chains and distorted demand for products.

Looking to the future, renewable energy helps to vastly reduce many countries energy dependence on nations such as Russia as well as helping to solve the climate crisis. To us it is the only solution for the long-term for policy makers.