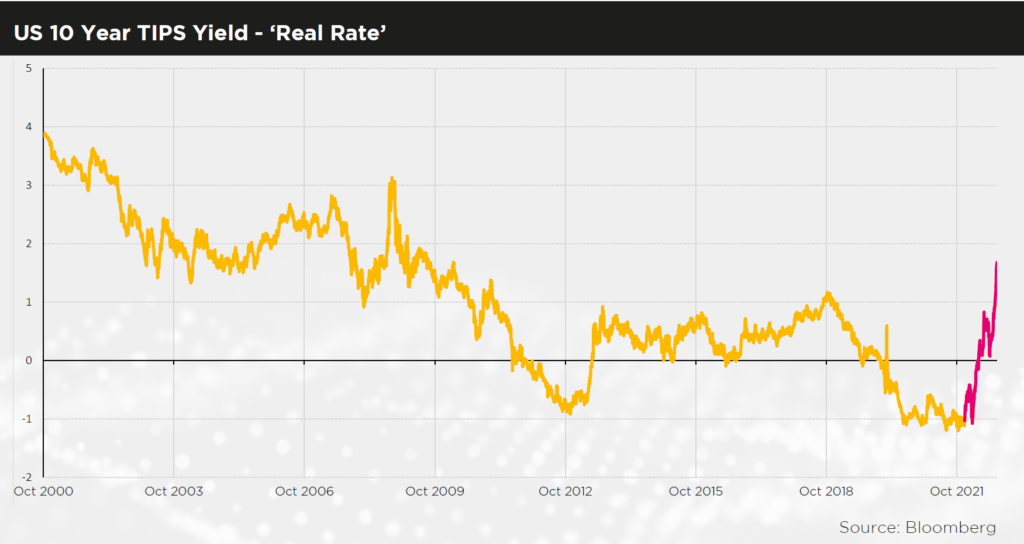

- The movements in the real (inflation adjusted) yield typify this – from 2000 to 2020 the real rate fell by roughly 5% – it has reversed half of this fall in just 9 months

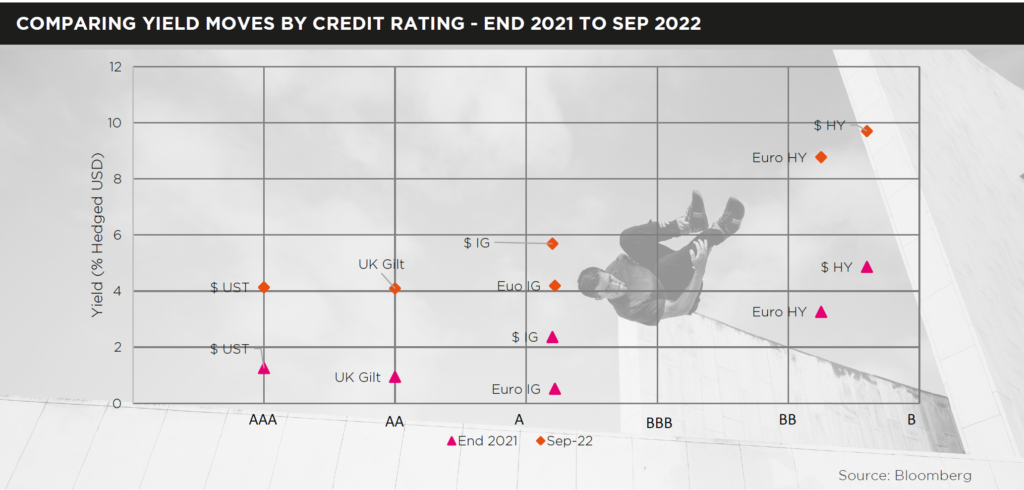

- However, on a forward looking basis, the long term returns investors should expect have dramatically improved following the moves in markets

- Our approach is to remain highly diversified, but over the medium term it is important to be ready to deploy capital into opportunities as they arrive

After years of concerns about high asset prices, a great reset is underway. After a decade of fighting low growth and low inflation with ever lower interest rates and more extreme monetary policy in the form of quantitative easing, almost all markets are moving lower as monetary policy goes into reverse.

This is a painful adjustment for investors, and we don’t yet feel that it’s complete, but there’s also good news: market valuations are moving back to levels where future returns are much higher. The repricing lower has been felt across equities, fixed income, listed property, infrastructure and gold. Some areas have yet to be affected simply because they haven’t had the time required to reprice, namely physical property, both residential and commercial, and private equity. We have been defensively positioned and diversified into strategies that are uncorrelated with bonds and equities to limit the downside of markets as they move lower.

IIt is hard to overstate the speed of the recent moves that we have seen in bond markets.

The chart below shows the real yield from US Inflation Linked bonds (TIPS).

The rate on the last page is referred to as a ‘real rate’, it is the interest rate an investor can receive after inflation from investing in a US inflation linked bond. It is the bedrock of the financial system, as it is used as an input to determine the value of what all real assets are priced at: equities, infrastructure, real-estate and gold are examples.

As this rate falls, the value of those assets tends to increase, it can be thought of much like an opportunity cost, as the opportunity to invest in a risk-free asset becomes less attractive (the yield you can achieve is falling), investors are forced into riskier assets to achieve their return expectations, pushing up the valuations of equities, infrastructure, and other assets.

Looking back at previous cycles, when we saw equities forming a bubble, such as in the late 90s period into 2000 when it burst, real yields were offering a healthy yield of 4% above inflation. This created a natural alternative to equities, providing investors a viable alternative to expensive stocks.

However, two decades of falling real rates, where they moved from 4% to -1% was fuelled by globalisation, accommodative central bank policy in the face of low growth and low inflation. This led to the ‘everything bubble’. Assets, from bonds, to equities, to wine, watches, crypto and NFTs gained value as investors increasingly sought out riskier opportunities in order to generate returns.

The post-COVID world has upended this world of low real rates however, with higher inflation, which has been fuelled by post-COVID growth policies, supply chain disruptions and de-globalisation. This has meant that real rates in the US have retraced half of their fall of the past 20 years in just 9 months.

We can link almost all of the fall in the S&P to this rise in real rates, as earnings have not yet responded to the global growth environment by falling.

Impact on Markets

Outside of this phenomenon, the UK also attempted its own experiment to fight the combination of slowing growth and stubborn, above trend inflation. The Truss government, attempted to stimulate the economy with a series of unfunded tax cuts via its ‘mini-budget’.

This policy decision making was adeptly summarised by the German Finance Minister Christian Lindner, who said:

What followed can only be described as market pandemonium, gilt yields in the UK surged, whilst the pound dropped rapidly, as global investors realised that these policies would, over the coming years lead to much higher debt-to-GDP levels in the UK, a decrease of creditworthiness and likely increase in the cost of servicing this debt. The moves in gilt yields were exacerbated by LDI schemes from pension funds, designed as a tool to help them match liabilities but not built for the outsize moves we saw in the short term in the markets.

This decision to expand government debt was so toxic, in a world of higher yields that it took a replacement of the Chancellor, and a reversal of most of the policies for the market to settle.

Looking Forward

On a forward-looking basis, however, the move in markets this year has greatly increased the return investors could receive from a portfolio of equities and bonds. Over the long term, the starting yield is a strong predictor of the return of the fixed income market, and so mechanically, as yields increase, the future returns an investor can expect to receive improves.

For equity markets, valuations can also tell us about the expectation for returns over the coming decade. Entering the most recent period of volatility, valuations of some markets sat in the top decile, meaning markets had rarely been more expensive.

Following the most recent falls in equity markets however, equity valuations appear far more reasonable.

Conclusion

The repricing we have seen this year across major asset classes has been rapid, and has caused significant pain, as real rates have caused the global financial system to adjust to a change of regime. We continue to be highly diversified and defensive, which has sheltered us from some of this pain. Over the medium and longer term, this repricing has meant that the odds for a period of better returns have improved for major asset classes, and it therefore remains important to be ready to deploy capital into opportunities.