- After one of the fastest rate hiking cycles in living memory, enacted because of elevated inflation across developed markets, many market participants have been surprised that economies have remained so resilient and we are yet to see a global recession.

- Even in the most rate sensitive sectors of the economy, such as mortgages, consumer behaviour has shifted, moving towards longer term fixed debt, which has reduced the sensitivity to rates. However, given some growth dynamics are showing signs of weakness, a diversified investment strategy that can adapt to rapidly changing market newsflow is important.

- The moves across fixed income and equity markets in 2022 mean that expectations of returns across major asset classes have shifted materially higher. In our view, cash is not a viable alternative to investing for those with a longer term horizon, given this shift in expected returns.

Outlook

There is an adage that economic cycles don’t die of old age, they are murdered by central bankers. In this vein, the first half of 2023 has been tricky for economic commentators, haunted by this phantom of recession, caused by central banks’ rapid rate hiking cycle. At the start of the year, many pundits, economists, and market participants were worried that the co-ordinated rate hiking cycle, enacted because of the worst inflationary crisis since the 1980s, would lead to a recession. The rationale and transmission mechanism are well understood; raising rates increases the cost of borrowing, decreasing the demand in an economy which cools the price increases caused by inflation. However, this comes at a cost to growth, which can ultimately increase unemployment, default rates, and tips economies into slowdown.

Indeed, after a decade of ultra-low interest rates, it was believed that the sugar-high of cheap debt would likely mean that the economy could not support vastly higher rates, and many of the companies and industries relying on cheap debt would get ‘found-out’, bringing this cycle to a close.

Are higher rates starting to bite?

Outside of liquidity events in the banking and pensions sector however, lending in the real economy hasn’t declined materially and nominal consumer spending has been resilient. Those who were calling for an imminent rise in unemployment or other labour market statistics, have to squint to see problems.

There are several reasons for this, but for consumers there are two important drivers as to why rate hikes have yet to bite:

(i) Consumers have borrowed money, often over multi-year periods at lower fixed rates for the long term as opposed to borrowing at prevailing interest rates.

(ii) Those with savings have benefited from higher interest rates on their deposits, allowing them to offset the problems of a higher cost of living.

Changes to the mortgage market

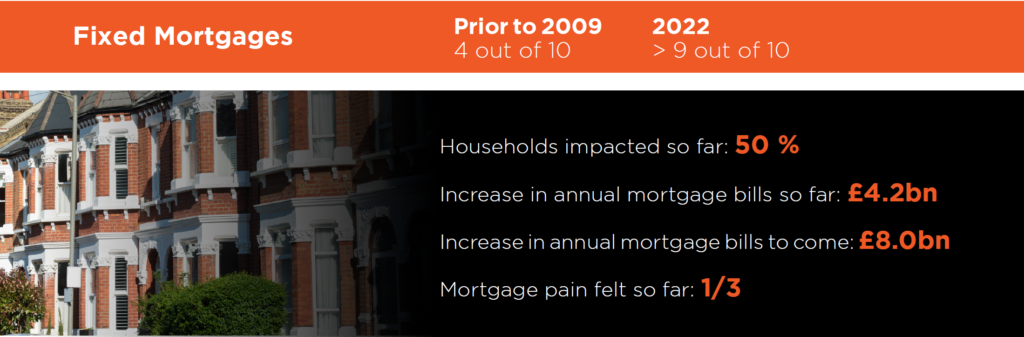

One example of why it is taking longer for the effects of rate hikes to be felt is how much the UK mortgage market has changed since the prior hiking cycle in the mid-2000s:

In fact, at that time more than 60% of mortgages were variable, meaning that mortgage rates shifted as the Bank of England moved its base rate and consumers felt the impact immediately. However now 96% of rates in the UK are fixed, primarily between 2-5 years, and as a result, higher interest rates take longer to be felt by households. It is estimated that in the UK, only half of mortgage holders have seen their mortgage costs go up by the second quarter of 2023 and that the UK has only experienced one third of its mortgage ‘pain’ that will be felt once rate hikes have flowed through. This means that, net-net, it will take longer this hiking cycle for the effects of the large interest rate moves to be felt. A similar pattern is true across other mortgage markets, and indeed for companies, a lot of whom have cash on the balance sheet (that they can now earn a reasonable interest on) and have fixed their debt at lower than prevailing rates.

This dynamic has improved growth prospects across developed markets, and if this cycle is to be killed it appears to have been given a stay of execution by the nature of longer, fixed rate debt in many markets that are typically most affected by rate hikes. We must continue to watch the data and be flexible in our views, and this delay to the recessionary dynamic has meant that in the short term there has been strong performance from equity markets, particularly as recent data on inflation has shown improvement. However, the effects of tightening will be eventually felt by economies, and hence we remain as diversified as possible, having strategies within the portfolio that can benefit from the heightened volatility of a recession if it were to occur, and having the ability to deploy capital back into risk asset classes if one does occur.

Is cash the answer?

Now that central banks have done a lot of work on raising interest rates as we discussed earlier, many clients are asking whether cash is a viable investment alternative to investing, particularly in lower risk multi-asset portfolios.

We do not believe that this is the case. Firstly, cash rates have been steadily climbing for much of 2022 and 2023, but they have only just now gotten to the point where the returns are significant (at or around 5% for UK or US based investors). For retail investors, it can often be hard to realise that 5% level, with banks offering much lower interest rates unless clients are willing to utilise fixed term deposit schemes. Further, to realise a return of 5% over a longer period than those fixed terms, it requires central banks to hold interest rates at these elevated levels, well above what they consider to be restrictive (and therefore negative for growth). In our view, if central banks were to hold interest rates at these levels for multiple years, it could cause a significant recession across developed markets, and history teaches us that when growth does slow central banks are typically quick to act in terms of reducing cash rates again.

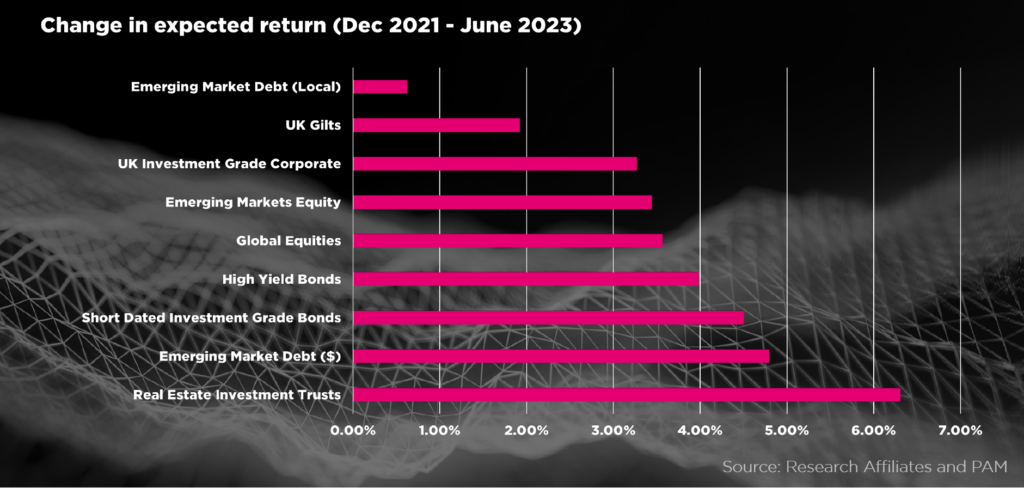

Finally, for us as investors looking for the best long-term outcomes, it is important to consider the expectation of future returns for major asset classes. Looking at long term (10+ year) expected returns as the chart below shows, we see that returns have improved significantly since the end of 2021 for many major asset classes. This is mechanically true in the case of fixed income investments. As yields increase on bonds, these become a sensible predictor of their long-term return expectation. These estimates are not meant to be a point in time forecast, but rather a good guide to what an investor could receive, on average over this time frame annually. Even allowing for forecasting error, it is worth considering how the odds for major asset classes have improved.

Conclusion

One of the features of markets is that when historic returns have been weak, forward-looking returns increase markedly. As we look out to the future, we note that the odds for returns across many major asset classes have improved, which is a function of the scale of the shock that markets experienced in 2022. This does offer hope, and to us it remains more important now than ever to remain invested, as over the long-term cash is unlikely to offer a viable alternative, despite in the short-term cash rates being higher than in the past decade.

Being tactical, diversified, and flexible in thinking has been vital to navigate the tricky markets of the last 18 months; and this continues to be the case given the unusual nature of this market cycle. As the lagged effects of interest rates take a longer time to bite, and dynamics such as longer-term fixed debt mean that economies are more resilient to interest rate hikes, it will take a longer time for the true scale of global central bank tightening to be felt on global growth. Therefore, the portfolios continue to be diversified, and adaptable to these changing market dynamics.