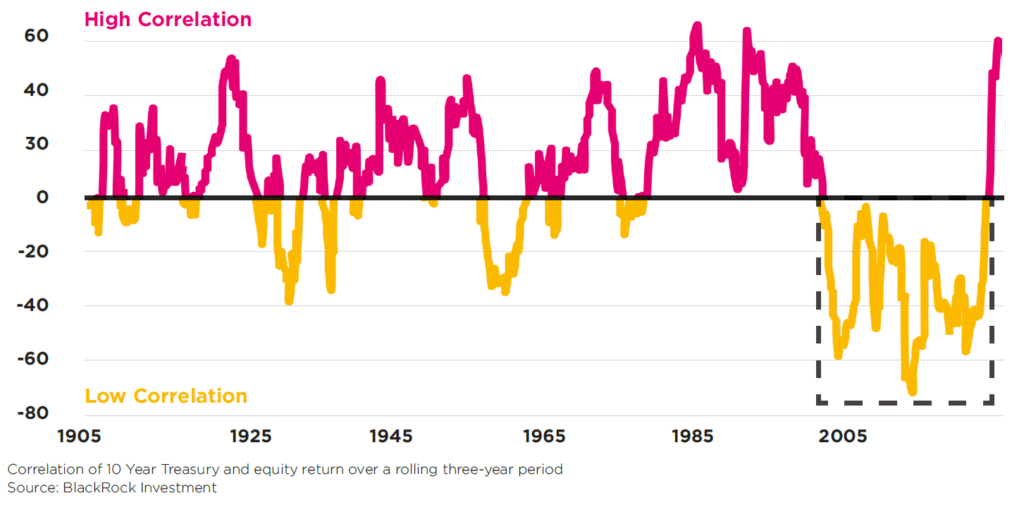

- The correlation between equities and bonds, which was negative for much of the last year, has shifted positive following the recent inflationary shock

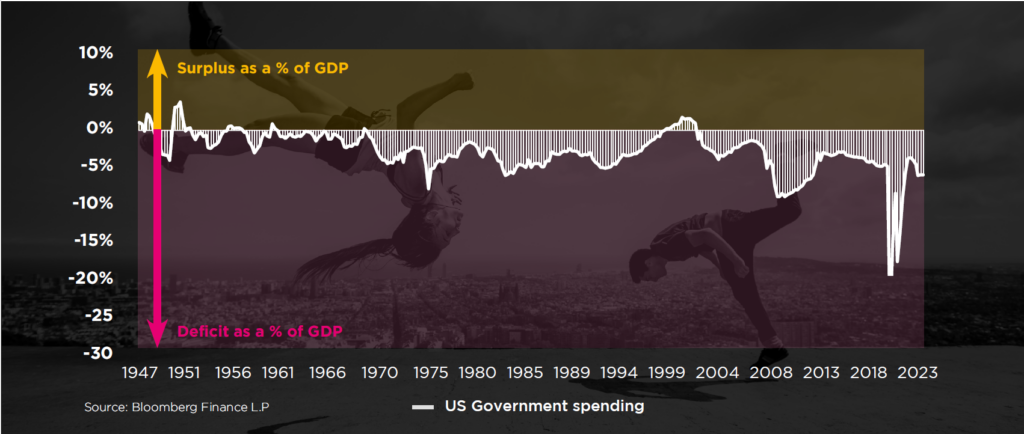

- Governments have also relearnt how powerful their spending is in terms of stimulating growth, which has pushed deficits to levels normally seen in a crisis

- Lessons from history teach us that the fight against inflation can be a lengthy process, particularly when government spending is high

- In this environment, whilst growth is strong and inflation is coming down it is important to remain open to the possibility that the path to inflation normalisation could be bumpy, and so it pays to have assets in the portfolio that can benefit from a higher or more volatile inflation environment

Outlook

After the rapidly shifting sands of markets in 2023, a soft landing, the ideal combination of lower inflation but no recession, has become the consensus. Portfolios have benefited from this improved outlook, but we continue to scan the horizon for potential threats.

After the fastest interest rate hiking cycle since the 1980s, there is increasing hope that central banks have prescribed just the right amount of tightening to bring inflation back to target whilst skirting a recession. If they manage to achieve this, it will indeed be an accomplishment. The history of these interest rate cycles shows how slim the odds are: around three in four have ended in recession. The last time the Federal Reserve pulled off this trick was 30 years ago, when Chair Alan Greenspan engineered a soft landing in the US in 1994/1995. The consensus for 2024 is that Jay Powell will achieve something similar, with inflation moving low enough to allow the Fed to cut rates whilst the economy slows but does not fall into recession. Under this scenario, we should expect multi-asset portfolios to thrive: bonds would benefit from lower interest rates and equities from a lower discount rate combined with satisfactory, if muted, earnings growth.

The strength of the market in the final quarter of 2023, with bonds and equities rallying after central banks signalled the end of interest rate hikes, offers a glimpse into how similar circumstances might play out. The S&P 500’s return in dollar terms exceeded 11%, placing it among the top 10% of quarterly returns since the 1950s. Perhaps more surprisingly, long dated US inflation linked bonds (TIPS) kept up with the S&P, before fading slightly in the last few trading sessions of the year. However, while all multi-asset investors welcome positive returns from both major asset classes, they should also acknowledge that their positive correlation can cut both ways, as it did in 2022.

Bonds and Equities correlation 1903 – 2023

In the chart above, we can see the correlation of bonds and equity has become much more positive over the last couple of years compared to the previous twenty. But when we look back further, we see that for most of history, back to the early 1900s, the equity bond correlation was positive. In fact, the 2000-2020 period was the anomaly in terms of offering diversification benefits from a simple equity and bond mix. One of the main drivers of this correlation is inflation, and it is our belief that the disinflationary era is likely over and that we have entered a regime of higher and more volatile inflation.

There are many reasons why this decade could bring more inflation, and one important driver we do see is government spending. In the post-COVID period, governments have learnt how potent their spending can be for growth. Typically, in the US over the past few decades, the fiscal deficit, which is the difference between government spending and tax revenues, has been slightly negative in normal economic times, and only expanded to around 6% during times of slowdown, as tax revenue fell and governments tended to spend more to address slowing growth. However, the COVID slowdown experience was one of a dramatic expansion in the deficit. This has persisted, with the current deficit at around 6%, equivalent to a crisis period despite growth being reasonable. This is a fiscal spending red flag, which could imply that inflation will be more volatile and could remain higher for longer.

Spending vs tax receipts as a % of GDP - a new era post COVID

While we are hopeful that central banks will triumph, it’s vital that portfolios are prepared for a resurgence in inflation. So, what can we learn from history about prior inflation shocks and how they were brought under control?

The IMF carried out a study of over the 100 inflation shocks around the world since 1970 to see what lessons could be learned. Their study focused on the 1973-82 period where many countries saw a surge in inflation due to the oil price shock but dealt with the problem with varying levels of success. Around 60% of countries managed to bring inflation under control within 5 years, with an average of around 3 years. But what can be learned from the 40% of episodes where inflation was still not under control after 5 years? The study found that the following conditions were present in countries with a prolonged inflation problem:

• Countries celebrated victory over inflation too soon.

• Countries had looser monetary policy.

• Countries had looser fiscal policy.

• Countries had inconsistent tightening policies.

This is why central banks are nervous about taking a victory lap before being certain that inflation is gone for good.

PORTFOLIOS FOR THE 2020s

If it’s the case that the correlation between bonds and equities will be higher this decade, then portfolios must be ready for this coming decade, rather than the last two. While equities and bonds remain crucial portfolio components, incorporating additional return drivers will continue to be important. This leads us to holdings in both alternatives, such as commodities and listed real estate, and diversifying assets that are uncorrelated with both bonds and equities. We think these opportunities remain compelling, so that diversification can lead to portfolios with less risk, without sacrificing returns.